Funny, though, that the CDC report, in its "Key Findings" summary, right at the top, says "Between 1999–2000 and 2009–2010, the prevalence of obesity increased among boys, but not among girls. There was no change however, in the prevalence of obesity between 2007–2008 and 2009–2010 for either boys or girls. It is unclear if the changes in the prevalence of obesity were associated with corresponding changes in energy and macronutrient intakes in children and adolescents during this time frame."

In other words, decreases of just 150 daily calories for boys, and 76 calories for girls over a decade haven't really made a difference in the numbers of kids who are fat. (Are those losses in calories offset by more sedentary time in front of a computer?) Interestingly, intake by boys ten years ago was 1,258 calories on average per day. Now, with an average of 2,100 calories as the mean consumed, teen boys are actually taking in less than the American Heart Association says is ideal for health.

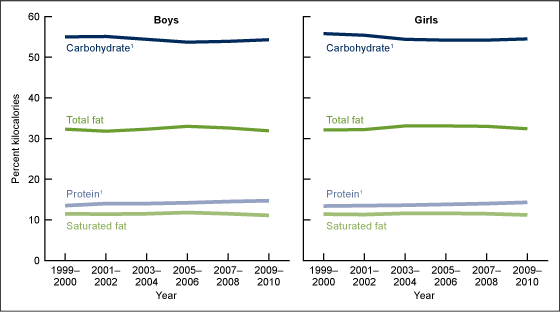

Then you look at the new study's chart about changes in what kids eat over the last decade, and, well, looks pretty consistent to me:

1Significant linear trend. SOURCE: CDC/NCHS, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Perhaps the headline should have been "Hype and Expense Countering Obesity Bring Few Results."

But our culture's enmity toward fat demands a war on "the epidemic of obesity" and continued revulsion toward those of size. A new book, What's Wrong with Fat? details all the negative implications of terms for larger people--terms of disdain rather than simply judgement-neutral descriptions. New York Times reviewer Abagail Zugler, MD. notes, "'fat' often implies the coexistence of sloth, gluttony and self-indulgence. 'Obesity' equals disease to medical professionals, while in the world of public health, it is a raging epidemic with substantial global mortality."

Except when it isn't. An impressive meta-analysis of thousands of studies recently found that overweight folks have the highest life expectancy, and those considered "grade 1" obese have the same mortality as people of normal BMI.

So why do we despise fat so much? Why is it worth millions of taxpayer dollars to combat this "epidemic"? The Stimulus alone dedicated $230 million just to anti-obesity ads. Could it have something to do with ease and grace? I'm just speculating here--Hollywood perpetrates the thin-as-beautiful model, obviously, and last week's Academy Awards highlighted to the nation the impossible standards placed before the public (with the refreshing exception of singer Adele). But it's more than that--our culture honors sports stars, ballerinas, and CEOs so accomplished they appear not to have time to eat.

Why? In our visual milieu, with TV and YouTube and HD movies from our own cameras, we're more exposed to images that contrast dynamic action with sluggishness. Thin people move easily. They gracefully alight from chairs, and energetically take on what's in their way.

Why? In our visual milieu, with TV and YouTube and HD movies from our own cameras, we're more exposed to images that contrast dynamic action with sluggishness. Thin people move easily. They gracefully alight from chairs, and energetically take on what's in their way.

Rolls of fat generally slow people down. Moving large girth requires greater strength and at times, difficult maneuvers. Communicating while out of breath detracts from content. Gov. Chris Christie, while brilliant and effective, has to deal with his weight publicly, a factor and distraction unconfronted by politicians who are more averagely shaped. Gov. Mike Huckabee, with a kindly heart, hopeful message and insightful mind, demonstrated his competence when he lost more than 100 pounds, writing about it in his book, Quit Digging Your Grave with a Knife and Fork. Some suspect that regaining part of the weight was a factor in his choice not to reprise his 2008 presidential bid in 2012.

|

| Jered Fogel with his old pants at Subway |

Obese people face problems beyond the usual challenges of life simply because they present a large form. A Feb. 13 New York Times story "Two-Thirds the Man He Used to Be, and Proud of It," describes England's Paul Mason, who actually lost two-thirds of his 980-lb. body weight via gastric bypass surgery, diet and exercise (though he remains limited by excess skin). (The online version of the Times story corrects the headline error, to "One-third the Man...") Meanwhile, a USA Today story details how Jared Fogel's life now centers around his new career as symbol for fast food giant Subway, after his self-styled sandwich diet whittled him from 425 to 190 lbs. Now the company and Jered have a symbiotic relationship, and its marketing chief credits him with a third to a half of the chain's growth over 15 years.

In other words, media shows us that obesity isn't a matter of health, it's a matter of gliding with effort versus ease. Of looking good, not just staying well.

"Let's Move!" barks first lady Michelle Obama, who took her healthy-eating campaign to Mississippi this week. She took a cue from her husband's tendency to sound preacherly when she lauded that state's improvement in elementary-age obesity: "Your schools did hard work, replaced their fryers with steamers, hallelujah, and started serving more fruits and vegetables and whole grains!"

As the champion of svelte form, known for her muscular arms, the First Lady adds to the assumption that agility and litheness are superior to ample girth, no matter the amount of strength and stamina the larger person commands. Fat implies gluttony and sloth nowadays, rather than an upper-class, pampered life. Perhaps thinness, a la Les Miserables, was once considered a sign of poverty and hopelessness, but in America, to the contrary, lower socio-economic-classes experience higher levels of obesity. Now it's the stylish, well-to-do who have time for gym regimens and preparing cuisine-du-jour featuring quinoa, macadamia nuts and acai. The poor, data show, spend more time sedentary in front of televisions and computers, munching "lower quality" diets of calorie-dense prepared foods.

As the champion of svelte form, known for her muscular arms, the First Lady adds to the assumption that agility and litheness are superior to ample girth, no matter the amount of strength and stamina the larger person commands. Fat implies gluttony and sloth nowadays, rather than an upper-class, pampered life. Perhaps thinness, a la Les Miserables, was once considered a sign of poverty and hopelessness, but in America, to the contrary, lower socio-economic-classes experience higher levels of obesity. Now it's the stylish, well-to-do who have time for gym regimens and preparing cuisine-du-jour featuring quinoa, macadamia nuts and acai. The poor, data show, spend more time sedentary in front of televisions and computers, munching "lower quality" diets of calorie-dense prepared foods.

To combat this trend, Mrs. Obama and television cook Rachael Ray joined in a healthy food cooking duet in Mississippi, and Michelle's "The Evolution of the Mom Dance" with TV host Jimmy Fallon garnered more than 14 million YouTube views. Her moves with Serena Williams and a gym full of kids in Chicago was another occasion to put down fat and boost people whose bodies can make easy gyrations.

I don't condemn the First Lady's campaign, or even her grinding in a circle, hands clasped over her head. Exercise is beneficial and moving freely, important. I don't think it unseemly for Mrs. Obama to demonstrate that no one is above striving for fitness, and to show that dancing can be fun, rewarding exercise (I'm a Zumba fan, myself). I also understand why gazelle-like movement is seen as more beautiful and desirable than the same actions by someone generously endowed (e.g. ballet is seldom performed by overweight dancers).

My issue is with the idea that obesity can be cured by a happy afternoon bopping in the gym, revising school lunch menus and putting fresh fruit stands on inner city corners. These things do no harm, but it's a waste to invest enormous amounts of tax money in them when there's scant evidence they'll improve public health or longevity.

Obesity is far too complex a problem to insist that choosing tangerines over Tootsie Rolls will make a major difference. All the hopeful praise of (to me imperceptible) declines in childhood BMI in a few locales negates the truth of the issue, and disheartens the many people who struggle earnestly to "make healthy choices" and include exercise in their lives but find they're still not dropping pounds permanently. We need honesty about the real extent of the "problem," and less panic and hysteria about an "epidemic" whose means of transmission is just not known.

I don't condemn the First Lady's campaign, or even her grinding in a circle, hands clasped over her head. Exercise is beneficial and moving freely, important. I don't think it unseemly for Mrs. Obama to demonstrate that no one is above striving for fitness, and to show that dancing can be fun, rewarding exercise (I'm a Zumba fan, myself). I also understand why gazelle-like movement is seen as more beautiful and desirable than the same actions by someone generously endowed (e.g. ballet is seldom performed by overweight dancers).

My issue is with the idea that obesity can be cured by a happy afternoon bopping in the gym, revising school lunch menus and putting fresh fruit stands on inner city corners. These things do no harm, but it's a waste to invest enormous amounts of tax money in them when there's scant evidence they'll improve public health or longevity.

Obesity is far too complex a problem to insist that choosing tangerines over Tootsie Rolls will make a major difference. All the hopeful praise of (to me imperceptible) declines in childhood BMI in a few locales negates the truth of the issue, and disheartens the many people who struggle earnestly to "make healthy choices" and include exercise in their lives but find they're still not dropping pounds permanently. We need honesty about the real extent of the "problem," and less panic and hysteria about an "epidemic" whose means of transmission is just not known.